The Myth of Musical DNA in Generative AI Outputs

We’ve argued before that attributing AI-generated music to specific training works via output analysis is fundamentally flawed. As outlined in our White Paper, this approach is neither technically feasible nor legally robust, and it leads to structurally unfair outcomes.

This is not a CORPUS position alone. In the following article, originally published on LinkedIn, Steffen Holly (Innovation Manager at Fraunhofer) explains from a technical and industry perspective why similarity in the output is coincidence, not causation—and why generative models only work because every input contributes to every output.

Whether two people are related and not just similar doppelgangers is clarified in cases of parentage and custody by analyzing both DNAs, because similar noses or ears alone are not proof of kinship. If we compare a song that was used to train an AI model with music generated by that model in terms of the traces that the training material may have left behind, we can only look at the similarity. This is because a unique type of DNA as a traceable identifier is NOT possible, and there are reasons for this. (I already wrote about this in July, but we need to dive deeper!)

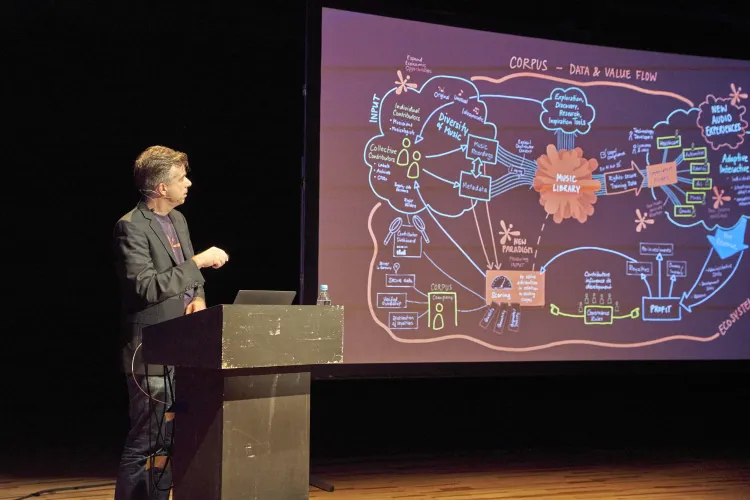

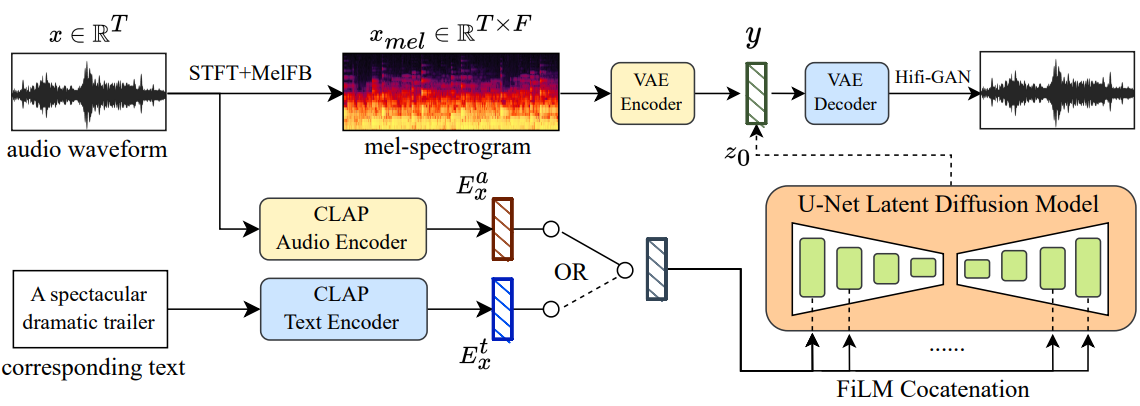

Generative models are not monolithic structures, but complex architectures that use references to take over six or more neural networks for the various aspects of generating complete pieces of music, e.g. in MusicLDM, where two audio speech models (CLAP Audio Encoder and CLAP Text Encoder) are used for pre-training, a latent diffusion model plus VAE encoder and decoder is integrated, and a Hifi-GAN neural vocoder handles the transformation of a spectrogram into the audio waveform.

Each of these individual models can be used in different versions within an architecture, resulting in many variations of an overall architecture. This example is from August 2023, and today's music machines are certainly no less complex. Furthermore, there are no publications of such architectures, which were still available in the early days of Suno, Udio & Co. If the trade secrets of the providers of such models are kept secret like the Coca-Cola recipe, no one has the opportunity to make a corresponding evaluation based on facts about the neural networks and models used in such systems.

A comprehensible assignment of influences and thus of rights between the AI result generated and the training material used for it is only theoretically possible under the following conditions: the system architecture of the generative model, including all exact versions of the individual neural networks and the exact weightings, is known, as is all information about the training material used for it. And even if this were to succeed, the next challenge would arise: for our unique neural network = brain, it is also virtually impossible to determine which of the songs we have heard have shaped our musical taste, when, how, and where. And has the song from kindergarten lost its effect on us in the meantime?

Fun fact: when a study demonstrated the memorization effect of Meta Open Source LLM Llama 3.1 by replicating 42% of the first Harry Potter book in the summer of 2025, Mark Zuckerberg announced shortly thereafter that they would consider how to keep the Meta open-source model “open”. For example, they would no longer publish weightings or parameterizations... because otherwise Meta could be sued for infringement of rights. None of the operators want to consciously take this risk. That would be a different matter than quietly stealing through the internet and saying, “I have no idea what I actually collected during my journey through the data world for my training!”

https://www.understandingai.org/p/metas-llama-31-can-recall-42-percent

An interim conclusion: The architecture and components of the models are unknown and are becoming increasingly complex, the parameterization itself is no longer published even in open-source models, memorization hardly works, and similarity is no proof ... And as if all that weren't enough, the way in which training is carried out also makes it impossible to attribute AI-generated music to the influences of the training material. First, the primary goal of training is not to produce pieces that are as similar as possible, but to learn from the features of the music and its structures for new creations. That is why music generation machines are not fed complete songs. For training, the models are shown enormous amounts of audio data as examples, in the order of millions of audio files. These examples are presented to the model in so-called “batches,” as a set of short segments from 5 to 50 randomly selected song segments at a time. The model processes these batches, and each short song segment individually has only a tiny influence on the parameterization of the model.

However, the resulting changes (delta) to the model's weights can be completely different depending on the values of the model weights before a particular batch. In addition, the cumulative effect varies depending on which specific other songs a particular audio file has been bundled with in a randomly assembled batch. By the time the model is used to generate audio, it has seen so many individual short song segments in random order and with random batch composition that it is no longer possible to trace the exact influence of a single song on the weights, let alone its influence on a specific output. Mathematically speaking, every audio file seen during training has the same influence on every generated output.

An example of the scale: with approximately 1 million songs divided into 20 segments and combined into randomly assembled batches of 5 segments each, this results in

\[ 43 \times 10^{138} \]

(the number 43 with 138 zeros) combinations with which the model learns in millions of iterations in the opaque structure of neural layers and networks.

The challenge of assigning rights to AI-generated music based on the training material used is comparable to determining

- the specific cotton flower from which each individual fiber of a T-shirt was made, or

- the exact proportions of scrap metal items collected at a recycling center that were recycled into a dessert spoon after being melted down.

"Assigning music rights used in AI-generated songs? I'll do that for you!" Any approach currently advertising this must have an answer to precisely these questions and, above all, must provide evaluated proof of its accuracy and reliability. Current state of the art: there is NOT A SINGLE comprehensible approach. Are the providers and promises for a solution to the dilemma naive or criminal... or both?

Now there is a new approach from a group of competent individuals called “neural fingerprinting”: https://soundpatrol.com/publications/blog-6#header

The extent to which the promise to determine all influences of the training material based on “neural” similarity represents progress is not (yet) clear based on the available information. As a test, I would try the following:

Anyone who creates music from the twelve available semitones, the defined scales, and the familiar structures builds on conscious and unconscious listening experiences and known theories, not to mention the standard chord progressions that make up 90% of popular music. Skillful or ingenious combinations of all influences mixed with a dash of personality and emotion (!) result in unique lyrics, melodies, and sounds. The “neural fingerprint,” the sophisticated and ingenious music similarity measurement machine, should be able to show in detail all “relationships and similarities” in a large music archive in terms of mutual musical influence regarding sound, melody, structure, chords, lyrics, etc. That would be fantastic, resulting in a perfect matrix of all influences and components from which successful music has benefited and “learned” or copied or “stolen”! You would have a picture of which ingenious melodies and structures of the great composers have been reused, how the beat developed from skiffle and country music of the 1950s, that all punk bands prefer chord progression XY, and that more than 90% of German songwriting collectives repeatedly use the same notes for their “great” chart hits, and which rhythm patterns rappers copy from classical, rock, or dance music. The functioning of a “neural fingerprint” would be scientific, technical proof that contemporary popular music fertilizes itself over and over again in an endless incestuous process and does not exist in a vacuum - in other words, nothing new.

With this technology, an AI-generated new song would reveal that 12.3% of the creation was influenced by a song X from 1984, which may not even be in the training material. But because this title X from 1984 is 66.8% inspired by the chord structure or snare groove of a jazz song Y recorded in 1959, and this is included in the training material, the algorithm spits out another 6.7% of this influence on the new songs... I don't even want to imagine how many songs, productions, lyrics, melodies, and chords with any percentage will come out for each individually examined song. What is a list of such influence worth then? And resourceful lawyers will comb through music archives, instigating lucrative copyright lawsuits based on the “neural fingerprint” of global hits and music history....

Please don't forget: only lyrics and melodies are protected from plagiarism by copyright, regardless of whether they are generated with or without AI. Sound concepts, authorship, and voice are easier to copy or “steal” and are difficult or impossible to prove based on any kind of similarity. Great technology does not automatically solve complex problems, and apparent accuracy can really cloud your brain.

Let's make it even more exciting: If, after the deal with Universal, UDIO says, “Well, we have the entire breadth of music as training material with the Universal catalog, we don't need to license anyone else, and this way we also get new material!”, then all royalties for AI-generated music go 100% to Universal anyway and from there into the black box. Okay, the processing of melody and lyrics in the copyright would not yet be remunerated, but before that there would be a battle of attribution between the individual songwriters and publishers or the local collecting societies... which is so stupid for the entire industry that one can only sincerely thank Universal for the “disservice.”

If, mathematically speaking, each audio segment of the individual tracks in the training material is to be evaluated with the same influence and weight in the creation of EVERY song by a generative music machine, then a simple formula suffices:

\[ \frac{X\% \text{ of total net revenue } Y}{Z \text{ tracks}} = \text{transparent} + \text{fair} + \text{efficient} \]

(X% of the total net revenue Y of an AI service divided by the number Z of tracks in the training material = transparent + fair + efficient for operators and accounting for rights holders)

And since the EU AI Act demands precisely this transparency regarding training material, and since implementation is technically and organizationally watertight and demonstrably feasible with state-of-the-art technology, then dear AI services “Surrender! Hands up and give me your money!” No more excuses, no more promises or lobbying back and forth from the tech bros that clouds our minds. There are 100% functional and proven technologies for precisely such comparisons, such as fingerprinting for upload filters, matching, and much more.

If, contrary to current knowledge, the impossible proof discussed here should become possible in a few years' time, then I will gladly tip my hat to it...

Just one more thing, the argument “We mark all songs with (a kind of) watermark and then we count the traces of it found in the creations of the music machines” comes up again and again. This doesn't even work in theory for various reasons:

- The watermark would have to be contained in its entirety in the digital audio every few seconds

- Such a “payload” would make the audio unconsumable

- Any not (yet) licensed AI service would exclude such titles from training, with another AI 😊

- There must be no old or new titles without watermarks in the world, or conversely, it makes no sense if only one rights holder “opts out”

- Any “secret” insertion of watermarks would no longer be possible

- But above all else: not a single watermark, no matter how strong, would survive a training process such as the one described above

- And at least two, but more likely a double-digit number of watermarks would overlap in every single AI-generated song.

Amen.