Why We Need a Learnright

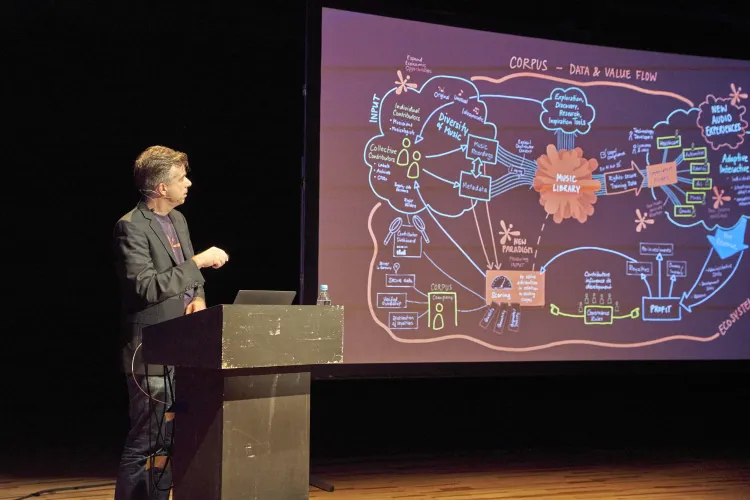

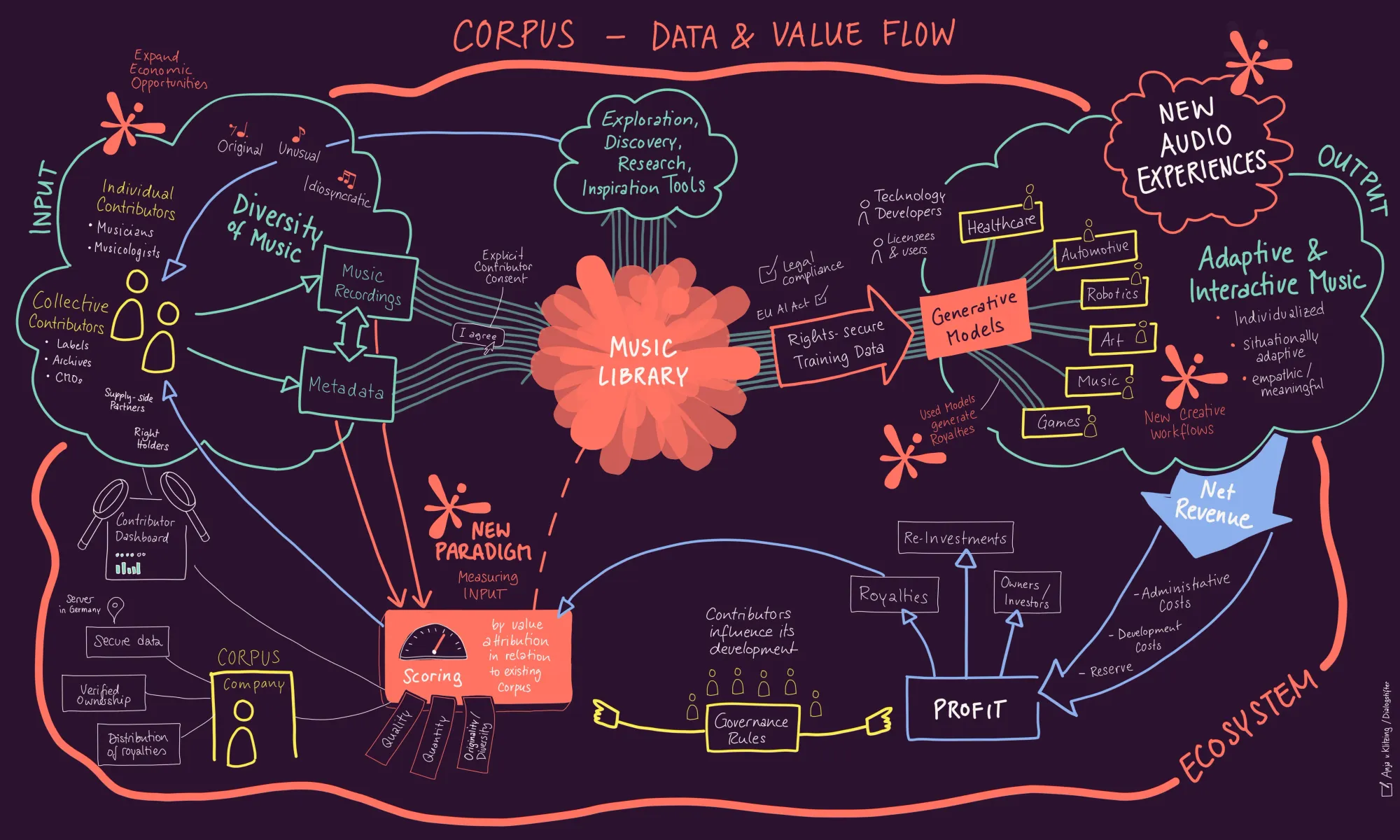

The CORPUS White Paper outlines a licensing and compensation framework for AI training that deliberately moves beyond the traditional logic of copying and use. It starts from the observation that existing copyright instruments struggle to account for value creation in generative AI systems.

This article takes a step further back. It asks why that logic is breaking down in the first place — and which previously unregulated category becomes visible through machine learning. A similar gap has recently been named by Frank Pasquale, Thomas W. Malone, and Andrew Ting in their proposal of a “Learnright”: a distinct legal concept for machine learning that cannot be cleanly reduced to existing copyright categories.

The Wrong Starting Question

In most current disputes around generative AI, the debate revolves around a single question: Was something copied? Copyright law has well-established tools for dealing with reproduction, distribution, and public communication, so the legal debate predictably follows that path. Plaintiffs point to copies; defendants argue that no relevant copies exist.

This pattern appears across jurisdictions: in the German GEMA v. OpenAI litigation, in U.S. cases against OpenAI and Anthropic, in the UK proceedings between Getty Images and Stability AI, and in policy frameworks that organize regulation and enforcement around the copyright classification of AI training.

What all these approaches share is an attempt to make machine learning legible through the concept of copying. That is the wrong starting point.

Why “Copying” Once Worked

Copyright is not an abstract theory of creativity. In its operative core, it is a law of economic exploitation. It protects works insofar as they are reproduced, distributed, or otherwise placed into markets. This does not deny the moral or personal foundations of authors’ rights; it simply acknowledges the limits of reproduction-based doctrines when applied to machine learning.

Historically, a copy was a distinct object: detached from its source, independently usable, and economically substitutable. Books, records, and later digital files mattered because copying and market participation largely coincided.

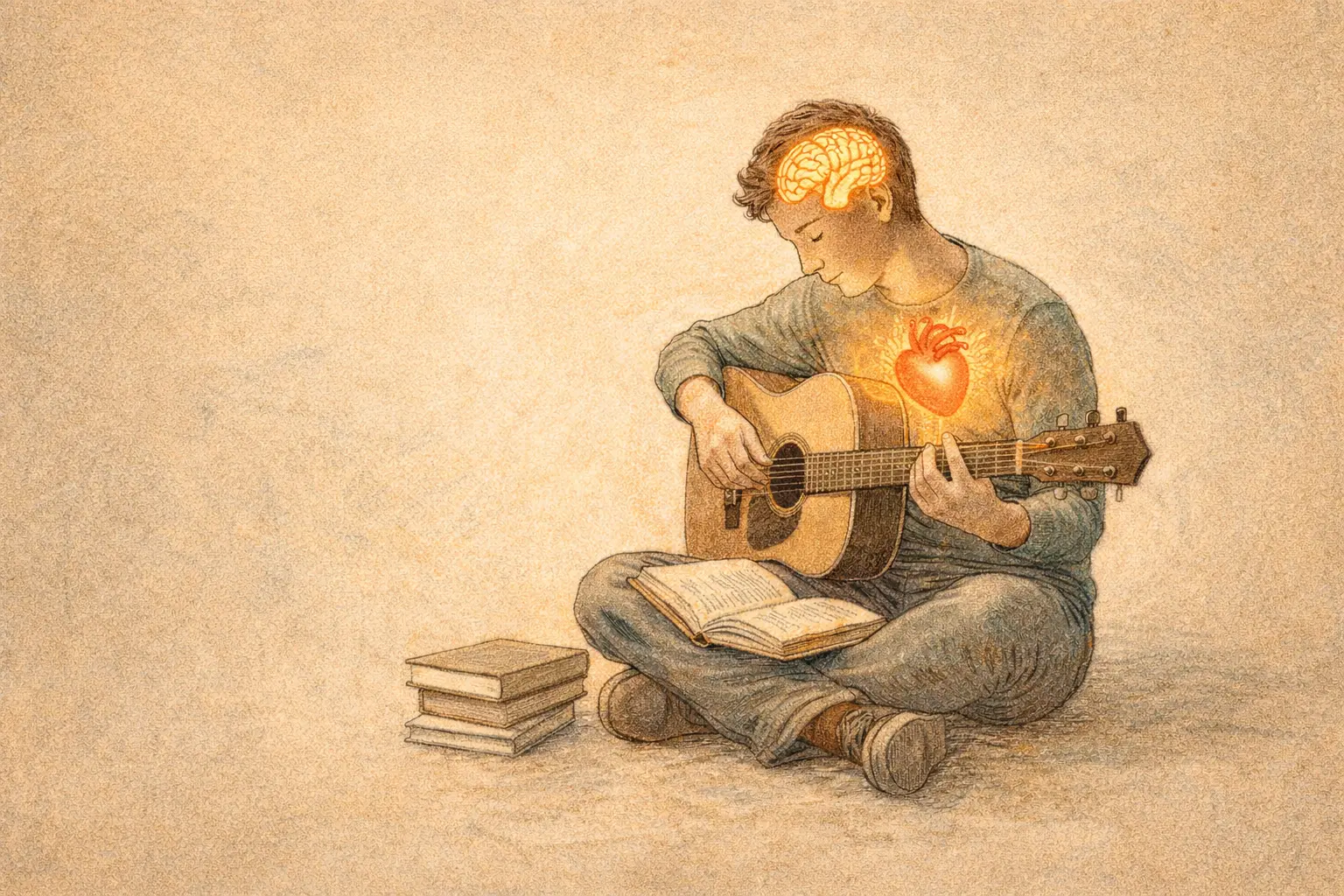

Learning never fit this logic. Humans have always learned from books, music, and images without this being licensed, not because of generosity, but because human learning did not constitute a market act. It produced no reproducible work object and no substitute. Learning remained legally invisible because it was economically limited.

What Changes with Machine Learning

Machine learning breaks this implicit assumption not because machines “learn differently,” but because learning has been externalized. Learning is no longer bound to individual human bodies; it is fast, massively scalable, permanently stored, transferable, and economically systemic.

By externalization, this article refers descriptively to the technical separation of learning from a human carrier and its fixation in a transferable system. For the first time, learning itself becomes economically consequential at scale. And for this process, copyright law has no dedicated category.

Why Copyright Starts to Misfire

Copyright offers three main points of attachment: reproduction, distribution, and use. It has no vocabulary for learning as such. As a result, legal and policy debates attempt to translate machine learning into familiar terms: memorization is treated as fixation, model weights are framed as stored works, and outputs are used retroactively to infer unlawful acts in training.

This is not primarily a matter of bad faith. It is a category error produced by the absence of an alternative framework. It becomes particularly visible where courts implicitly assume that a trained model is a kind of archive, merely a poorly accessible one. Technically, this is incorrect. Legally, it functions as a stopgap.

Copying Is Not Where the Value Is

Training undeniably involves technical copying. Data is stored, loaded into memory, transferred, and processed. But these copies are transient, technically necessary, not independently usable, and not economically substitutive.

Copyright law itself already recognizes this distinction. In many jurisdictions, temporary copies without independent economic significance are excluded from copyright relevance.

The economic value of training does not lie in reproducing individual works, but in their statistical aggregation, transformation, and abstraction into a parametric system. The result is not a work or a collection, but a system with behavioral capacities. Copying is a technical precondition, not the locus of value creation.

Outputs Are the Proper Test

This does not mean that copyright concerns disappear. When generative systems produce outputs that are substantially identical to protected works, those concerns are legitimate. Near-verbatim lyrics, recognizable images, or reconstructable texts may constitute unlawful use or substitution.

But this assessment belongs at the output level. Learning itself is not a use in the sense of a directly copyright-relevant exploitation of a work. Treating training as use shifts copyright into a domain it was never historically designed to regulate.

Why There Has Never Been a Learnright

The absence of a “learnright” is not an oversight. It was coherent with the historical conditions under which learning took place. Here, learning does not mean subjective experience or consciousness, but the formation of generalized capabilities through exposure to information.

Human learning was slow, embodied, non-transferable, and non-scalable. For these reasons, it could not displace markets. Machine learning can—not because it is more intelligent, but because learning itself has been externalized and industrialized.

The Learnright proposal responds to this rupture by explicitly distinguishing machine learning from human learning and arguing that the former can no longer rely on the latter’s historically implicit freedom.

What a Learnright Would Have to Address

A learnright would not replace copyright, nor would it legitimize infringing outputs. It would need to distinguish learning from use, separate training from exploitation, and acknowledge that value creation in machine learning is collective and non-isolable.

The central question would no longer be which work was copied, but under what conditions externalized learning is permissible, and how the resulting value should be allocated.

Why CORPUS Exists

This is where existing compensation models begin to break down. Traditional licensing presumes identifiable works, traceable uses, and direct exploitation. Generative AI relies on distributed statistical contributions, non-reversible influences, and system-level value creation.

CORPUS does not start from copies or individual works, but from contributions to a learning system. It does not claim legal authority and does not replace existing law. It is an infrastructural attempt to operate within a regulatory gap for as long as that gap remains unaddressed.

Conclusion

As long as learning is governed as if it were copying, courts will rely on fragile technical assumptions, developers on fragile legal ones, and copyright will be stretched beyond its conceptual limits.

The CORPUS White Paper proposes an infrastructure for navigating this tension. The notion of a Learnright names the gap itself. This article has aimed to explain why that gap exists at all.

The question is not whether copyright must be abolished. The question is what kind of legal concept becomes necessary once learning is externalized, scalable, and economically decisive.